The India Story remains one of quality product sold at affordable prices to the nameless mutineers going about their daily grind.

Nobel laureate V. S. Naipaul, an author of Indian origin, described India as a place where “a million mutinies” occur at any given point of time. An apt description for a country where a red signal at a traffic light is merely a suggestion; where ten people die every day on the railway tracks of Bombay (2x those killed from terrorist attacks all over India); and where there are a reported 150,000 suicides every year. The randomness of daily life hits you from the moment you brace an Indian sunrise. But in addition to this Brownian movement which Naipaul captured with his eternal phrase, there is a certain creativity, a certain birth and re-birth that would make Joseph Schumpeter proud.

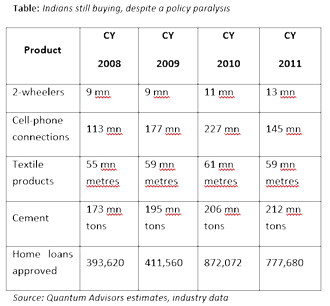

The headlines in CY 2011 captured the policy paralysis in New Delhi. The UPA-led coalition government (headed by a stiff Prime Minister whose silence has damned him into public disrespect) froze the big-ticket capital expenditures by private enterprise to Absolute Zero. But, below the headlines, the million mutinies of small-ticket consumption kept the India story humming to ensure a > 7% rate of growth. And India's government controlled Public Sector Undertakings (PSU's) continued their capex.

Manufacturers of consumer goods are doing well. There is competition and price-cutting as they establish their presence in the growing Indian market for soaps and shampoos - but there is demand.

True, iron ore mining collapsed: because the iron ore mining licenses were alleged to have been obtained by fraudulent means. The big-ticket expansion of ports, airports, telecom, and real estate projects all slowed down as the government agencies were busy investigating claims of nepotism and corruption.

India's feudal industrialists were in a grumpy mood for all of CY 2011 and have made enough statements that they will expand in the western countries where the “business environment” is “better”. Good luck to them in dealing with slow-growth markets in the western world and rising pension costs. While the feudal lords slowed their capex, rural consumption was in mutiny mode and did pretty well - despite a 200 bps hike in interest rates during the year.

While Robert Brown and Joseph Schumpeter would be pleased with what they saw, the sell-side was rattled. The truth is that xl sheets like linearity. Black Swans is what you tell the widows about once their savings have been decimated. Disappointment of the Jim O'Neil kind (India was the country within BRIC that the originator of BRIC was most disappointed with) comes partly from assuming linearity and partly from not quite getting what makes India tick.

The India story is not about the business leaders profiled in glossy business magazines - many of whom “made it” because of their ability to work the system. Neither is the India story about the ability to set up a debt-laden, flag-in-every-city India empire. It is about businesses selling quality product and affordable prices to the nameless and leaderless mutineers going about their daily grind.

I am Anna - with more money to spend

Anna Hazare galvanized the fight for a Lokpal (People's) Bill that would oversee the fight against corruption. While the “I am Anna” slogan captured the imagination of India's youth, lower class, and middle class - there was no “Be Indian, Buy Indian” slogan driving the India consumption story. Obeying Nike, they just did it.

In a country where the average per capita income is USD 4 per day, if you earn an extra 40 cents per day, you will spend it. The much-maligned National Rural Employment Guaranty Act (enacted in 2005) guarantees one person in every house hold a job for 180 days at a minimum wage of INR 100 per day (approx. USD 2). One-third of all jobs must be given to women. While most criticize NREGA as a corruption-ridden system where men are being paid to sit at home and drink liquor, we think there must be some good out of this. Firstly, a person will not leave the comfort of his home (and liquor bottles, as the city folk claim) for a job in a city where he needs to live at the mercy of some slum lord unless he is paid a lot more to do. So, NREGA has raised the minimum wage price of Indian labor. Secondly, NREGA has allowed people to stay on in rural areas - thus reducing the pressure on the strained infrastructure of India's creaking cities. Both are positives.

That extra salary at lower income levels has resulted in more buying power. And, for now, there is sufficient capacity in Indian industry to meet demand. A lower capex cycle will not hurt growth in the near term. Indian industry is famous for squeezing out capacity from existing machines. Less cumbersome brownfield expansions could meet growing demand for the next 18-24 months. And feed growth in company profits.

But, eventually, India will need to see the large capex in power and infrastructure for the economy to get back to a wishful 8% rate of growth in GDP. The capex could come either by way of large projects - or by companies building their own infrastructure if they see no government will to do so. In the 1990's when India's growth outpaced the central planners ability to build supporting infrastructure, the Indian companies built their own jetties, their own power plants (running on diesel), and their own roads around the factory gates. Not an efficient use of limited capital, but it kept India moving and business humming.

Since the failure of government to deliver infrastructure is something that India's entrepreneurs are used to (Infosys has built its business delivery mechanisms assuming zero government support), the shock in CY 2011 - in our humble opinion - has been the inability of the government to deliver cheap national assets at the doorstep of India's pampered industrial barons for their further exploitation.

Ultimately, it's in the micro

With all the macro noise around us we remain bottom-up stock pickers. Armed with a mandate to look after your capital, at the end of the day we remain disciplined value managers.

Our challenge remains: to understand and analyze the businesses; to decipher the valuations ascribed to these businesses in the stock market; and to understand the ability of the management to guide these businesses in challenging times - the unflinching question of leadership is crucial.

Yes, you can make money in India over the next decade. But the smartest investors, blinded by greed, may not see their fair share of profits for the identical risk taken by them as co-shareholders with many of India's creative founding families.

So, go ahead and make the “risky” decision to invest in the volatile stock markets of India, knowing that it is our job as disciplined, long term, value investors to assess the risks of managements and valuations. To reduce your risks so that you can get your fair share of profits as the growth of the Indian economy generates significant investment returns over the next decade.