“It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it. If you think about that, you’ll do things differently” – Warren Buffet

Global institutional investors ignore risk when they invest in India. The recent bribery allegation against the Indian conglomerate and its founder along with employees of institutional investors, illustrates the governance challenges of investing in illiquid private assets in India. Macro risks and market risks can be priced and managed over the long term. However, governance risks can seldom be priced and the reputational costs of backing ‘bad actors’1 can be severe.

Despite the incident, we believe the opportunity set in India is wide and diverse. Global Investors can make sensible, risk adjusted returns by attempting to control risks which can impact their reputation by considering these issues:

Volatility is not the only risk

Most investment professionals equate risk with volatility. But risk is a fundamental issue that questions the very basis of the existence of an enterprise. And risk can show up over decades. Impatient asset allocators seeking ‘alpha’ and quickish returns can hop over to their next job if they ‘get it wrong’ and Boards of Trustees and members of oversight committees may retire long before risk ‘impairs the portfolio’.

Eventually the ultimate beneficiaries – the pensioners or family members – are left nursing the losses from the fundamental error of equating volatility with risk.

One of the biggest risks institutional investors faces is that of ‘governance’ – or lack of it. What type of companies are they investing in the public markets? What is the quality of the founders they are implicitly trusting when they invest in private assets? How have the companies they invest in secured permission for their infrastructure projects – a mostly opaque process riddled with bids and government-approved agreements? Which developer partner are they working with when they invest in real estate projects be it for warehousing, data centres, or commercial/residential real estate projects?

Reputation risk of backing Crony Capitalists with passive investing

Global Institutional Investors invest across markets passively by replicating an Index or buying an ETF. The key benchmark indices do not have a governance screen to weed out ‘bad actors’ 1. Index providers tend to react to a governance event post facto by removing the company from the Index when the damage is already done. Passive investors are failing in their fiduciary duty and exposing themselves to reputational risks. India investing should be active, with a clear focus on governance. A ‘Be Good. Do Good’ approach to investing in India can help deliver sensible returns.

Global Institutional Investments in Indian Private and Real Assets

India needs trillions of dollars to meet its sustainable growth aspirations. India’s Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) have risen, however, unlike in China where global corporations drove large investments into China to manufacture and operate, in India, a bulk of the FDI is investments by global investors into private equity, venture capital, infrastructure and real estate which gets classified as FDI.

Foreign investors have allocated twice as much to private markets and real assets over public equities2. India has received increased flows from foreign investors in infrastructure and real estate investments on the back of an improving regulatory eco system, emergence of investment trusts for operating assets and a growing pool of diverse asset operators3. However, we are unsure that investors have been duly compensated for the illiquidity and governance risks in private assets. Many instances of the quality of the founders being implicitly trusted, the nature of the infrastructure contracts being secured and the choice of the real estate developer partner suggest to us a dilution of risks that has impacted eventual returns.

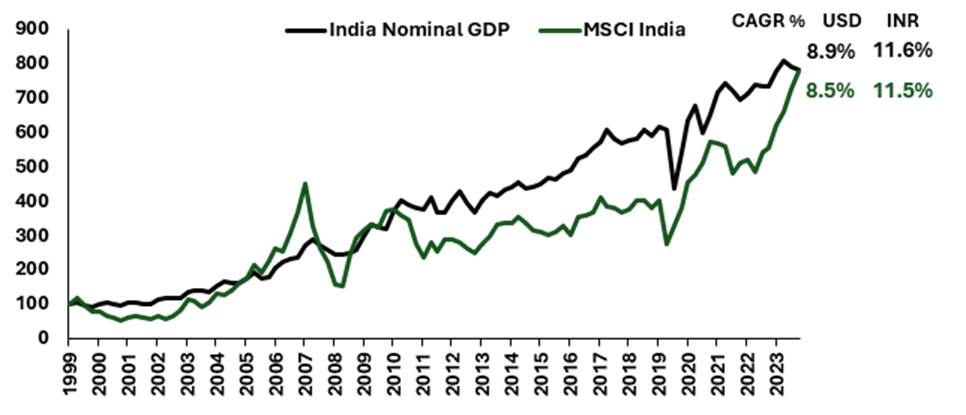

On the other hand, this real GDP growth since 2000 has led to double-digit growth in nominal GDP (CAGR 11.6% in INR) / (8.9%in USD ), which is reflected in the Indian Stock Market Returns as represented by MSCI India Index ( CAGR 11.5% in INR) / 8.5% in USD ).(data as at September 2024, see the charts at the end of the article). Despite India’s requirement of private capital, unless allocators to private investments assess and price the governance risk correctly, investing in public equities may offer a superior risk/reward outcome.

Indian capital market regulation and rule of law

There will be questions raised against India’s economic investigative agencies, the regulator and the stock exchanges on what the US Department of Justice (DOJ) and US Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) discovered about an Indian company which the Indian agencies missed. Investors need to be reassured that the Indian agencies are independent and able to gather all the information they need to arrive at a decision about rule of law being maintained. The regulatory ecosystem should have enough deterrence, checks and balances to protect investors from governance risks. Alas, the onus to manage the reputational risk of governance issues is in the hands of the investor and/or their local partners and not on any reliance on mathematical formula of standard deviation and volatility.

An indictment of a corporation, but not an indictment of Indian capital markets

Poor governance, fraudulent accounting, and unchecked greed are not restricted to emerging markets like India. Enron, Exxon, AIG, Lehman, Madoff, Wirecard, Parmalat, Theranos were some of the many shocks to the western capital markets.

This incident may be indictment of a corporation, but this should not be seen as an indictment of the Indian capital markets. Over the years, SEBI and the market intermediaries have created a robust capital market infrastructure which has increased investor confidence, seen a surge in listings and market volumes and has witnessed a diverse participation from the biggest global institutional investors to the smallest domestic retail Indian individual.

We believe Indian public equity markets are relatively ahead of the curve as compared to many other global exchanges in terms of compliance, disclosures, operations and settlement.

The knee-jerk reaction of such an alleged failure of governance can be to redeem out of all India investments thereby missing the opportunities for significant compounding long term returns from investing in India – an act of throwing the baby out with the bath water.

The more studied and measured response to such an event is to adopt and/or to find external managers who have an established process of governance-screening embedded in their research and investment selection criteria.

Global Investors can make sensible, risk adjusted returns by attempting to control risks which can impact their reputation.

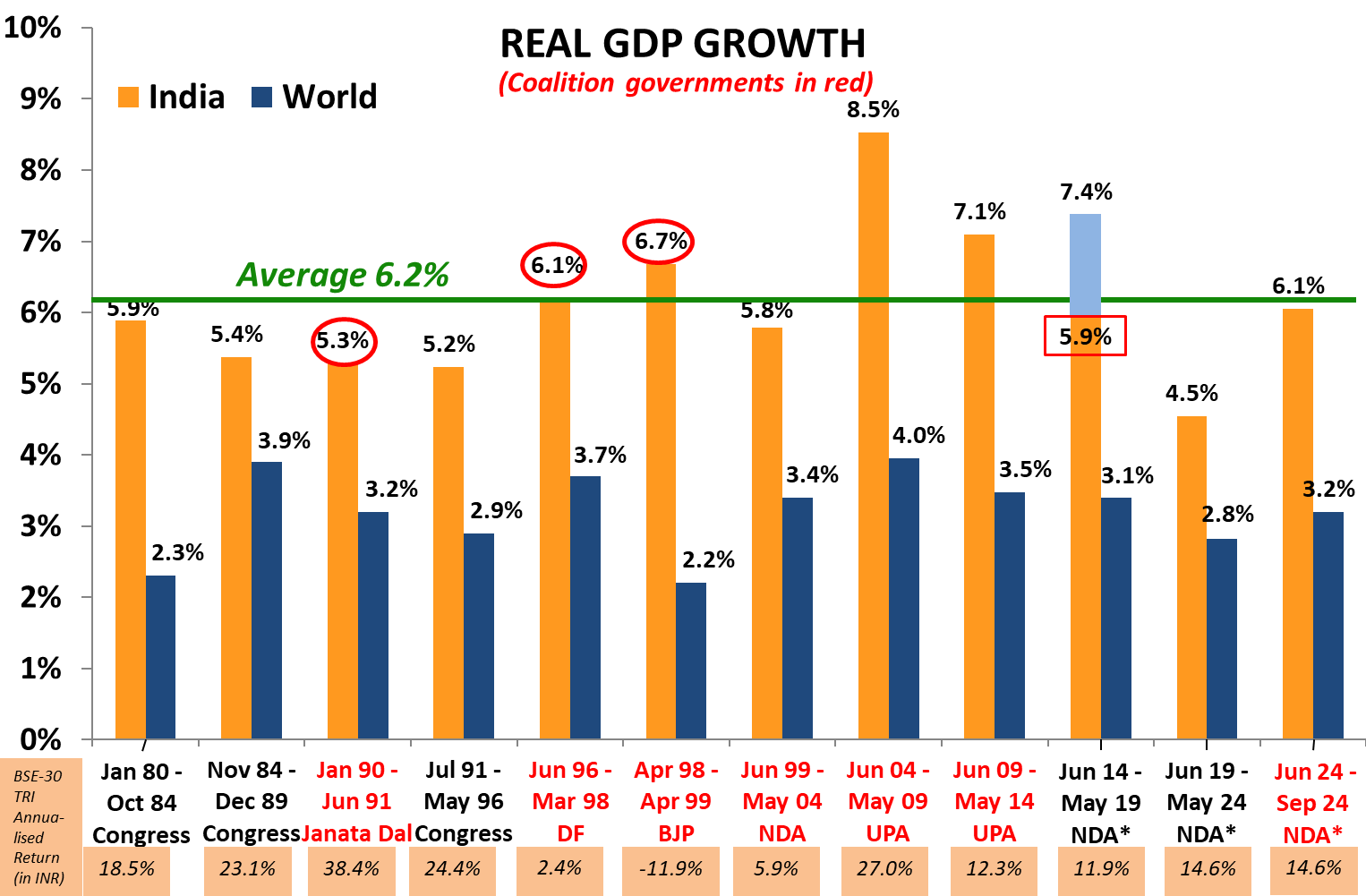

Chart 1: India Real GDP growth has averaged between 6.0%-6.5% across different governments. Since 2000, the real GDP growth has averaged 6.2%; similar to its average since 1980

(Source: Worldbank, RBI and www.parliamentofindia.nic.in as of September 2024. Note: The number in red rectangle is from a changed data series starting Jan 2015. While a “superior” series, there is no comparable number to equate the “New” with the “Old”. Most economists deduct 0% to 1.5% from the “New” to equate to the “Old”; therefore, under Modi, the GDP has been at 5.9% at best matching the 5.6% under the BJP-led coalition government of Vajpayee that resulted in a rout for the BJP at the time of the next election in 2004. Please note that data used for World GDP from 2021 is a median annual estimate since quarterly data is not available and India GDP data is governments second advance estimate released at the end of November 2024)