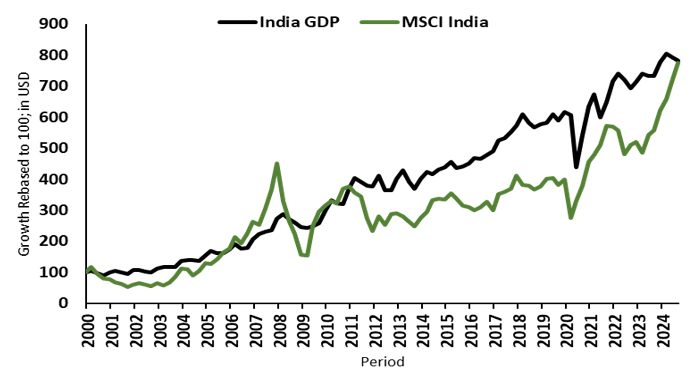

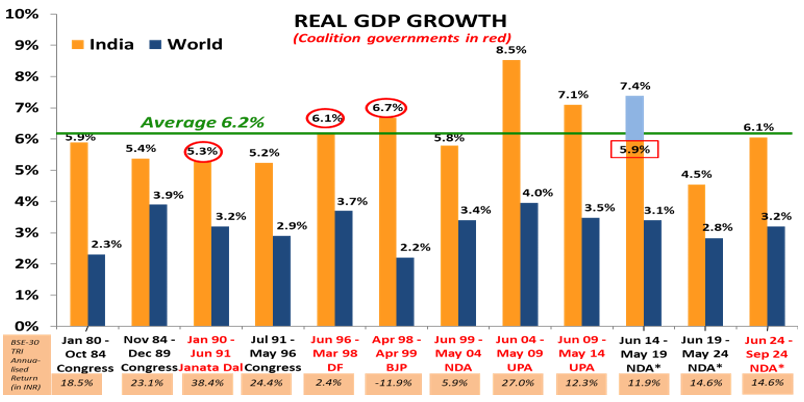

India needs sustained long-term growth to pull people out of poverty, create jobs for the young, and boost incomes to widen the consumption base. At Quantum, we have long held India’s potential real GDP growth rate to be 6.0%-6.5% (6.2% is the average since 1980). This pace of growth, though twice that of world GDP, may not be enough to achieve India’s aspirations of becoming a middle-income country and creating meaningful jobs for its youth.

The Indian state, the Indian economy and most Indian corporations do not fall under any of these categories and hence are unlikely to be directly impacted by Trump’s policies.

India is a big net importer of Oil and Gas and can technically benefit from a supply hegemon like US. India does not have any stake in the high technology world. India does not make high end chips, has not developed its own large language models, does not even have its own 5G telecommunications protocol, and has no major technological prowess in new energy – renewable, battery, storage. India runs an overall trade deficit. India runs a small trade surplus with the US in goods and a larger trade surplus in services and we will discuss that in detail below. India is not part of any multi-lateral trade agreement and has not ‘gamed’ US free trade. We believe India is not a ‘geo-political threat’ to the US. Also, India has never been dependent on US congress’s benefactions to manage its own security interests.

Chart 1: India GDP growth has averaged 6.2% since 1980

Source: World bank, RBI and www.parliamentofindia.nic.in as of September 2024. Note: The number in red rectangle is from a changed data series starting Jan 2015. While a “superior” series, there is no comparable number to equate the “New” with the “Old.” Most economists deduct 0% to 1.5% from the “New” to equate to the “Old”; therefore, under Modi, the GDP has been at 5.9% at best matching the 5.6% under the BJP-led coalition government of Vajpayee that resulted in a rout for the BJP at the time of the next election in 2004. Please note that data used for World GDP from 2021 is a median annual estimate since quarterly data is not available, and India GDP data is governments second advance estimate released at the end of November 2024. The graph is only for representation and understanding purpose and does not assure any promise or guarantee that the historical performance is indicative of future results.

Can India then grow at +7% for a sustained period? The answer to this proverbial question on India’s potential growth rate depends on the period in which the question was asked:

- In the 1980s, the hopeful answer would have been 5%.

- In the 90s, post-liberalization, hopes had risen for a sustainable 6% growth rate.

- During the ‘Goldman Sachs - BRIC’ mania of 2004-2011, it was India’s birthright to grow at 9%.1

- Morgan Stanley’s ‘Fragile Five’ in 2013 smothered it down below 8%.2

- ‘Ache Din’ in 2014 raised hopes of 8% again

- In ‘Atma-Nirbharta’ and ‘Amrit Kaal,’ many seem to be settling for ~6%.

Our long-term assumption of 6.0%-6.5% real GDP growth comes from a very simple analysis. Assuming India’s Gross Domestic Savings (GDS) of ~30% of GDP and the incremental Capital-Output ratio (ICOR - capital required to get a unit of growth) of ~5, the potential growth (GDS/ICOR) gives us 6%. This ~6% gets balanced by the negative aspects of inefficiency in the government sector and household savings, and the positives of attracting excess foreign savings into India.

Technically, India should be growing faster than this suggested potential. Efficiency is improving (India’s ICOR is lower) 3; Indians are saving more in risk assets4, and India is attracting capital from abroad across Foreign Direct Investments (FDI), Foreign Portfolio Investments (FPI), Foreign Borrowings (ECB), and from the Indian diaspora (remittances and deposits) (see chart 4). However, these have not resulted in growth sustaining above 7%.

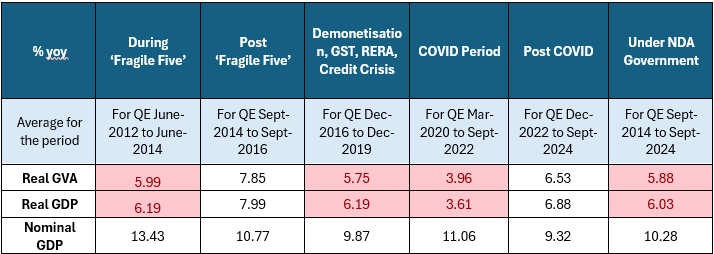

Table 1: India GDP growth has been below potential in the last 10+ years

(Source: CMIE Economic Outlook, QE=Quarter Ended; shaded for levels below 6.5%; GVA = Gross Value Added; ‘Fragile Five – refers to period when India was bracketed with countries which were vulnerable due to high external current account deficit and inflation in an era of tightening FED policy and strong dollar; RERA – Real Estate Regulation Act; Credit crisis refers to the financial system impact post the collapse of Il&FS, September 2018; Post COVID - we assume the quarter post September 2022 to be period from which y-o-y numbers are not impacted by covid period base effects; Under NDA government which started in May 2014, GDP data taken from June-September 2014 quarter)

For the quarter ending in September 2024, the year-on-year growth rates were as follows: Real GVA at 5.6%, Real GDP at 5.36%, and Nominal GDP at 8.04%. This represents a decline of more than 1.5% in both real and nominal terms compared to September 20235. This decline has sparked a debate on whether India is experiencing a cyclical or structural slowdown.

Some attribute the slowdown to tight fiscal and monetary policies, while others point to the incomplete recovery from the lack of income and job growth both pre- and post-COVID. A prominent economist and former Executive Director at the IMF described the slowdown as ‘surprising and inexplicable,’ attributing it to ‘India’s Deep-state inspired policy’ of high taxation on income, trade, and capital6.

All the above explain the current slowdown and it seems to be a mix of cyclical and structural reasons. However, the debate on whether the slowdown is cyclical or structural yet hinges on one’s growth expectations. If one expects sustainable growth above 7%, then India appears to have been in a structural slowdown for many years. Conversely, if one believes India’s sustainable potential is between 6.0% and 6.5%, the current decline might be seen as cyclical.

However, considering India’s young demographic and low per-capita levels, achieving a growth rate of 6% should be relatively straightforward. Therefore, a decline below this level, as observed in 2019 and now, is indeed a cause for concern.

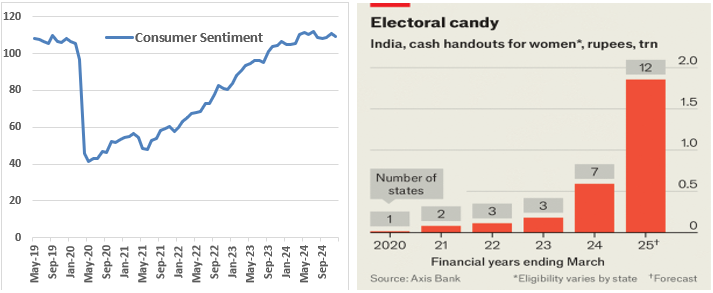

We do see some short-term remedies on course. Fiscal policies at the state level, across all parties in power, have turned towards supporting incomes and providing subsidies. 16 out of the 28 states now offer some form of direct income transfer to women. Various research now estimates that >0.5% of state GDP is spent only on women through bank transfers and other schemes7. This should alleviate some of the income concerns that seemed to have held back demand. This is the harsh reality, and politicians are the first to react to it. They know that over the last decade, growth has been weaker, incomes have been modest, and job growth hasn’t kept pace with the labor force. The only way to maintain social stability and political relevance is to provide cash transfers and income support, as the leader of the opposition, Rahul Gandhi, promised to voters as ‘khatakat’ – (like the brisk whirring sound of an ATM machine dispensing cash)8. Consumer sentiment and overall employment, which were already on the upswing and back above pre-COVID levels, should improve further, driving demand.

Chart 2 and 3: Consumer Sentiment should get a boost on cash handouts

(Source: Consumer sentiment - CMIE Economic Outlook; Data till December 2024; Chart from The Economist, article Jan 23rd, 2025)

Monetary policy may have sent the first signals of choosing domestic monetary policy over a fixed exchange rate. Allowing the INR to move freely and weaken against the US dollar is indicative of this stance. This needs to be followed up with liquidity infusion and a rate cut in February, which may further weaken the INR and ease economic conditions. We would expect these measures to address the ‘cyclical’ headwinds.

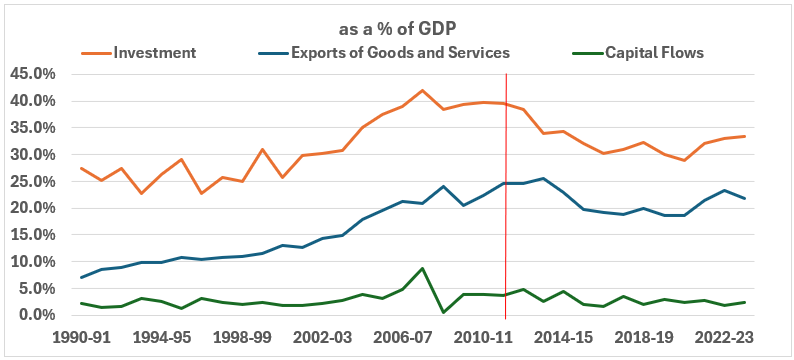

For India to grow at +7%, according to the ICOR formula, we need Gross Savings or investments to be at 35% of GDP, up from the current ~30% levels. This increase in investments and savings needs to come from higher domestic capital investment, an increase in the global share of exports, and a higher share of global savings as capital flows.

We saw this happen for close to two decades from 1991-2011, when investments rose due to an increase in domestic capacity creation, a rise in export share, and global capital flows. This does not need ‘big bang’ reforms now. India and India’s ‘Deep-state’ may know what it takes to try and drive growth above potential. It was a combination of receding government control, simplification of taxation, freer goods and services trade, and a recognition of treating risk capital in a fair, transparent, and consistent manner which lifted India’s potential growth from 5% to >6%.

Chart 4: Can going back to policies of pre-2011 get growth above potential or do we need a ‘New Deal’?

(Source: CMIE Economic Outlook; Annual GDP at current market prices; Investment=Gross Capital Formation; Total Capital Flows; Data till March-2024 )